- The Lonely Laborer /

- Save hand work, Save old media, Save humanity /

- Faceless Labourers /

- 8 Hours /

- Satoru Aoyama Demands a 30 Hour Week /

- Beautiful Flags /

- The Age of Disappearance /

- The Waste of Labour Power /

- News From Nowhere /

- Record /

- Map of the World /

- Embroiderers /

- About Painting /

- Man Machine /

- Death Song /

- Roses /

- Working with Grandfather /

- Glitter Pieces /

- Horse in the Studio /

- Crowing in the Studio /

- Still Life /

- Landscape /

-

Map of Europe

2016

-

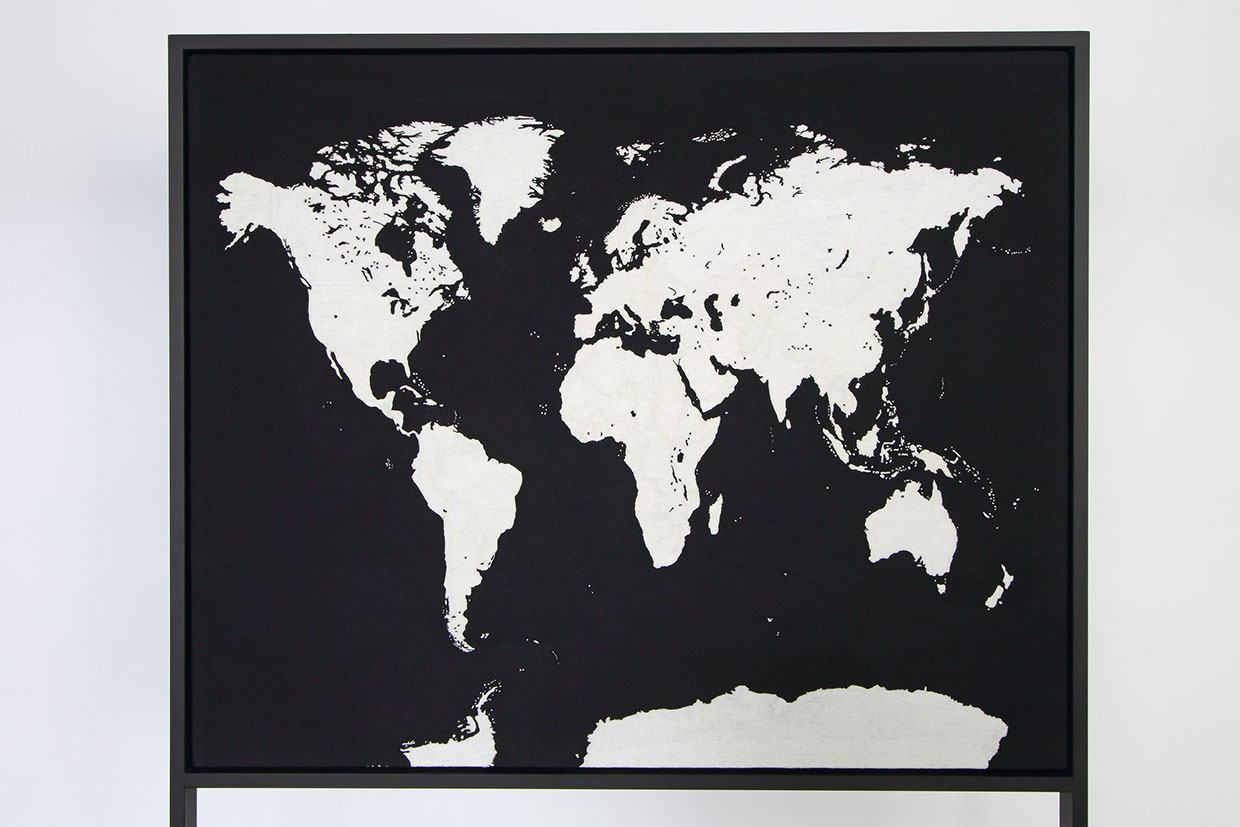

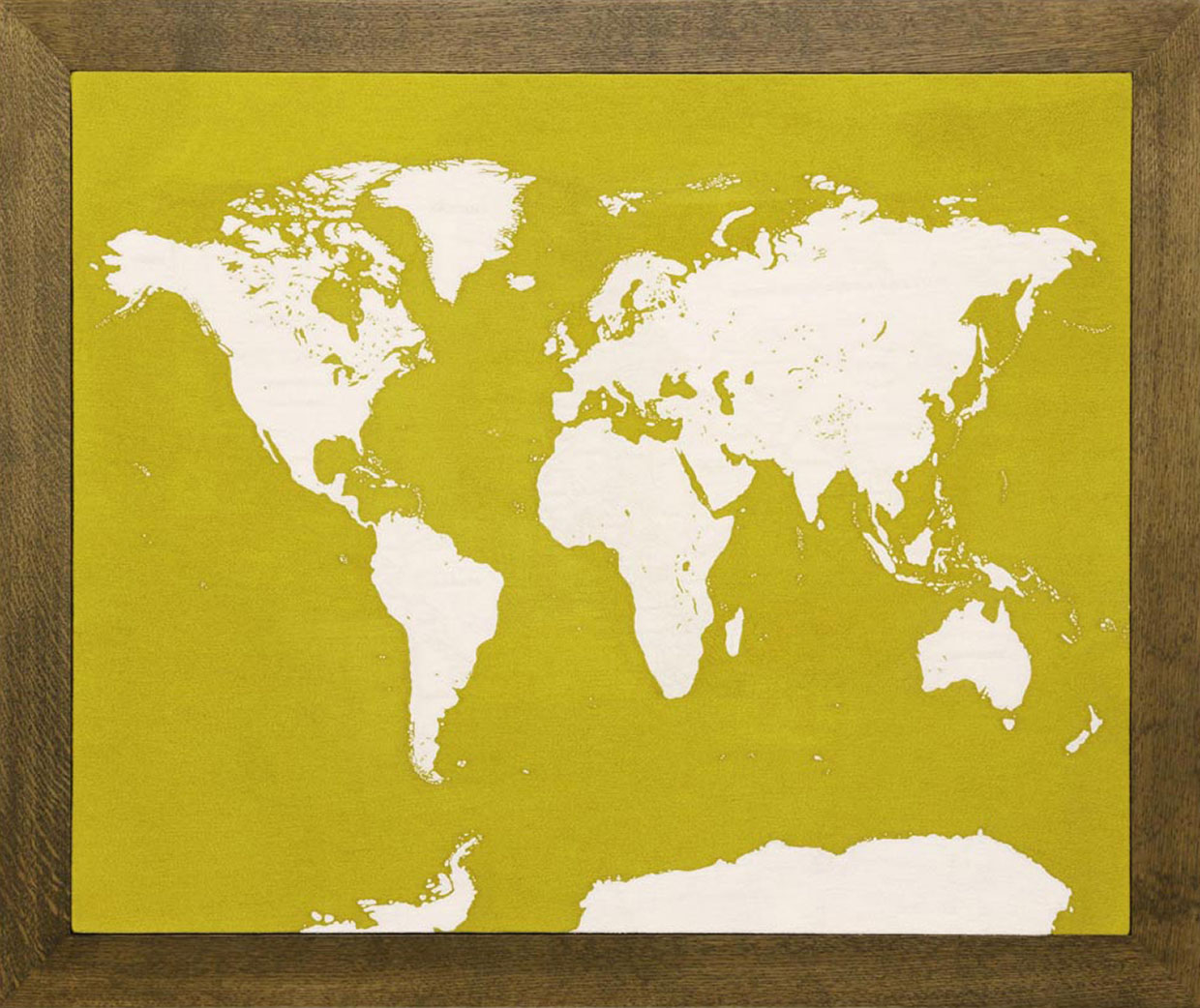

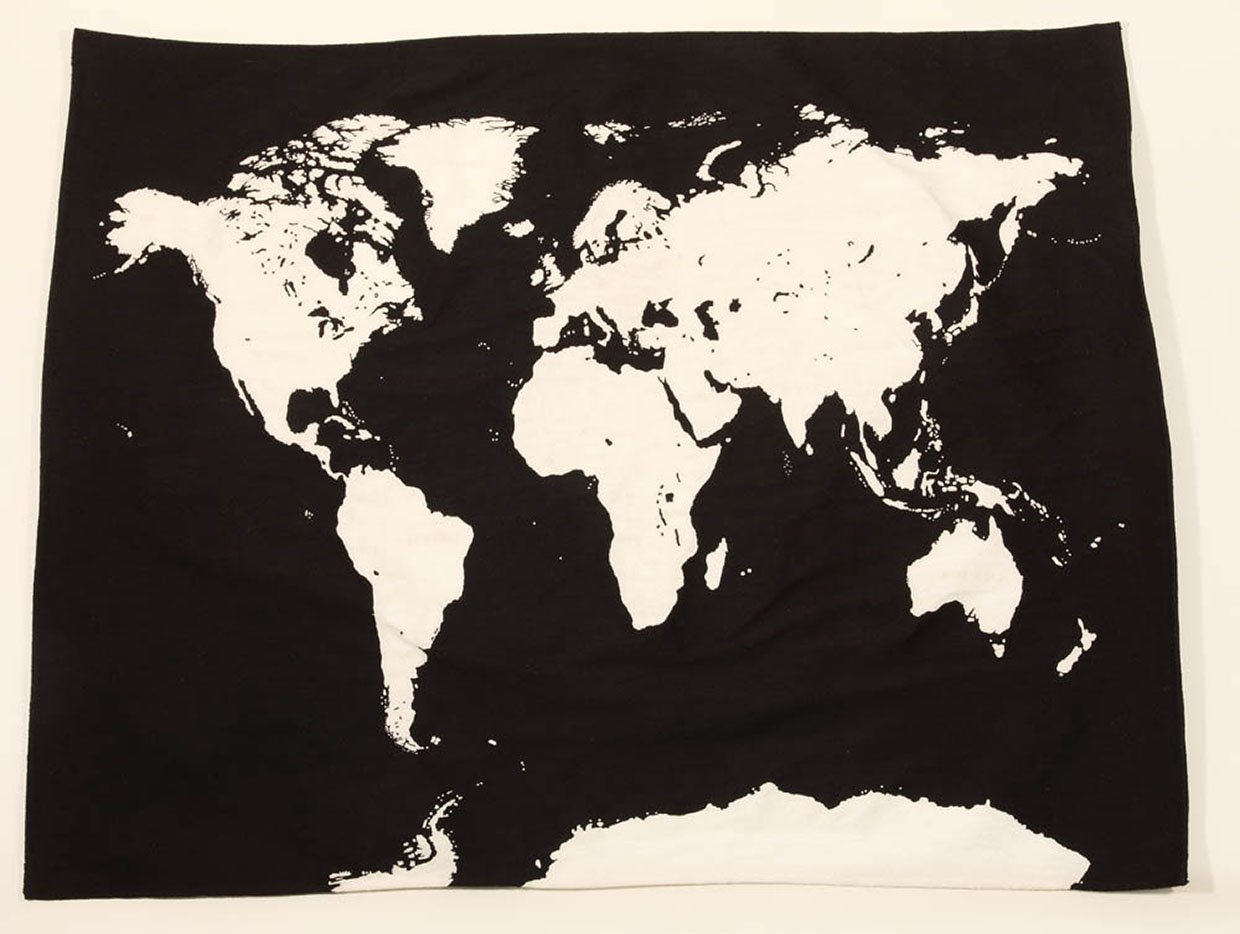

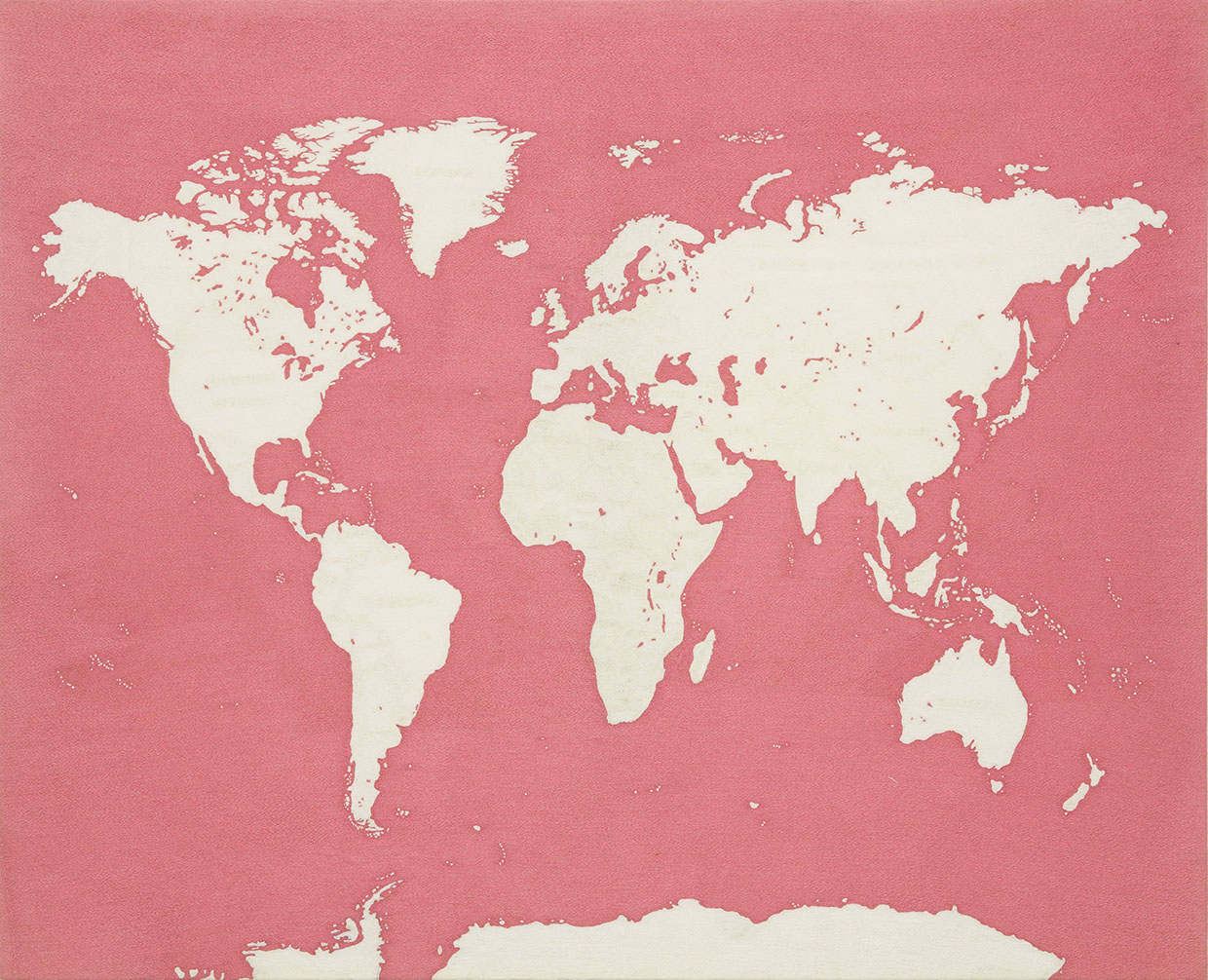

Map of The World (Dedicated to unknown Embroiderers)

2016

-

アーティストたちの世界地図 (ドローイング) / Map for the artists (drawing)

2014 -

-

Map of The World (Dedicated to unknown Embroiderers)

2013

-

Light and Patterns 1

2012

-

Map of The World (Dedicated to unknown Embroiderers)

2015

-

Map of The World (Dedicated to unknown Embroiderers)

2015

-

Map of The World (Dedicated to unknown Embroiderers)

2014

-

Map of The World (Dedicated to unknown Embroiderers)

2013

-

Map of The World (Dedicated to unknown Embroiderers)

2014

《 Map of the World (Dedicated to unknown embroiderers)》について

この作品はイタリアの前衛グループ、アルテ・ポーヴェラの一員として知られるアリギエロ・ボエッティの刺繍による世界地図作品、“Mappa”に対するオマージュとして長年構想していたものです。近年ロンドンのテイト・モダンで回顧展が開催されたり、ドクメンタ13で取り上げられたりと、批評的な側面から再評価されているボエッティですが、”Mappa”に対する自分の最初の印象は「良くできた工芸品」でした。それは決して肯定的な意味だけではありません。実際、“Mappa”が最初に発表された時、この作品は多くの批評家から工芸的だと酷評されたそうです。それは当時、アートはコンセプチュアルで高尚なものであり、技術を意味するクラフトは機能的な日用品である、というようにアートとクラフトがはっきり棲み分けされ、両者の間には価値的にも批評的にもヒエラルキーがあったことに由来します。(このヒエラルキーが形成された背景には社会に於ける女性の立場も関係しています。)もちろんボエッティは自分のアイデアを実現する為に必要な技術を職人に依頼するという、現代アートでは多く見られる方法で制作を行うコンセプチュアルな作家ですが、彼がアフガニスタンの首都、カブールのホテルを改装し、刺繍家たちを集め、制作を依頼した、という実際の背景を知らない者にとって、”Mappa”は国の領土にそれぞれの国旗の柄を当てはめた、刺繍による世界地図でしかありません。”Mappa”は当時にしては作家の個人性が極力排除された表現です。加えてボエッティは時に海の色など、作品にとっての重要な選択を刺繍家たちの判断に任せたりもしました。それ故、アートに携わる多くの人々に作品が工芸的だという印象を与えることとなりました。しかし、社会とアートを取り巻く状況が変わった現在では、ここに見られる「共同性」はボエッティの作品を再評価する大きな一因となっています。

一方、大学でテキスタイル科を専攻し、ミシン刺繍による作品を発表し続けている自分にとって、このアートとクラフトの関係性は常に重要な問題で、クラフト的な手法を肯定しながらアートの文脈に自分の作品を位置付けることは、現在まで続く制作の動機のひとつと言えます。それ故、ボエッティの活動の全容を知れば知るほど、”Mappa”を実際に縫っていたアフガニスタンの女性たちに対して同じ刺繍作家としての興味が湧いてきました。そして彼女たちの職人としての技術や決断、作品に捧げてきた時間を、同じ非西欧圏に住む、いち刺繍作家として世界地図を縫うことでより深く理解できるのではないかと考えました。ボエッティの名前と作品は既にアートヒストリーの一部として認識されています。しかし、この歴史上決して表舞台に上がることのない名もなき刺繍家たちの活動に光を当てることは、多文化主義を理想ではなく、あらゆる問題を内包しながらも実感を伴った現実として生きる自分たちにとって、より意義があることなのではないか、と考えたのが新作、“Map of the World (Dedicated to unknown embroiderers”を構想したきっかけとなっています。 また、2012年の秋から冬にかけて滞在した、青森でのアーティスト・イン・レジデンスの体験もこの新作に大きな影響を与えています。青森では、まず現地で刺繍作品を制作する意義を見つける為に、津軽に伝わる刺し子のひとつ「こぎん刺し」のリサーチから始めました。「こぎん刺し」は魔除けの柄等を着物にあしらった幾何学模様が特徴的な美しい刺繍ですが、元来、木綿の使用が農民に禁止されていた時代に、着物に使われている粗い麻布の布目を、刺繍で埋めながら防風性を高めるという機能的な目的から生まれました。つまり「こぎん刺し」の背景には厳しい寒さと経済的な困窮に耐える為の東北地方の女性たちによる苦悩と工夫の歴史があります。青森の滞在中には、現在でも伝統を守りながら刺し子をする職人さんや、伝統に新しい感性を吹き込もうとする若い職人さんとお話をする機会があり、刺繍というものが特定の時代や場所によってどのような意味を持つのかをあらためて考える契機となりました。また弘前こぎん研究所では、作者不明の古くて美しい刺し子を手に取って見ることができました。このような過程を経て、青森でのアーティスト・イン・レジデンスでは最終的に、伝統的な刺し子のパターン等が暗闇で浮かび上がってくる、一見真白な画面の刺繍作品を制作し発表しました。この作品では都市における伝統の「消失と再生」が大きなテーマとなっており、これは戦争に翻弄されながら、カブールで地図の刺繍を続けた女性たちに対する興味へと繋がっていきます。

“Map of the World (Dedicated to unknown embroiderers)”は、ミシン刺繍による世界地図です。明るい場所では何の変哲もない白地図ですが、暗闇の中では国名と国境が浮き上がります。浮かんでは消え、消えては浮かぶ国境が、観る人のどのような思いに触れるのか、作者の自分にはわかりません。ただ、この刺繍作品がもしも作者の存在を超えて、たとえ「名もなき刺繍家」が残した作品としてでも存在し続けられるなら、それは作者にとっても作品にとっても、この上ない幸せなことのように思えます。

青山悟

On Map of the World (Dedicated to unknown embroiderers)

This work, in the planning for many years, is a tribute to “Mappa,” the series of embroidered maps of the world by Alighiero Boetti, a key member of the Italian avant-garde group Arte Povera. Boetti has been critically reassessed in recent years through a retrospective exhibition at London’s Tate Modern and featuring at dOCUMENTA 13, but my own initial impression of “Mappa” was that they are “well-executed craftworks.” That does not necessarily only have a negative meaning. In fact, when “Mappa” was first shown to the public, it was apparently castigated by many a critic for being “craft-like.” At that time art was supposed to be something lofty and conceptual, and crafts that signified techniue were regarded as functional everyday objects. Art on the one hand and crafts on the other were segregated in this way, originating from the fact that between the two there was a hierarchy in terms of respective value and criticism. (The background that formed this hierarchy is also related to the position of women in society.) Boetti was of course a conceptual artist who produced his work using methods widely seen in contemporary art today, and hired craftsmen to implement the technique necessary to realize his ideas. However, for people who are unaware of the context in which “Mappa” came about, which is that Boetti was renovating a hotel in the Afghanistan capital of Kabul and commissioned a group of embroiderers to produce embroidery for him, “Mappa” would be nothing more than an embroidered map of the world showing national territories colored with the designs from each of their national flags. In line with the times, “Mappa” contains hardly any sign of the artist’s personality. Boetti would also sometimes entrust important decisions about the work, such as the color of the sea, to the embroiderers. This is the reason the work gives the impression of being craft-like to many people who are involved in art. However, in today’s world where the circumstances of society and art have changed, the nature of the situation where a group of people pull together towards achieving the same objective demonstrated by the “Mappa” project is one of the major reasons Boetti’s work is being reevaluated.

For me as someone who majored in textiles at university and since then has continued to exhibit works of sewing-machine embroidery, the issue of the relationship between art on the one hand and craft on the other is always important, and the positioning of my own work in the context of art at the same time as I affirm my craft-like techniques could be described as one of the motives of my artistic practice to date. The more I see the big picture of what Boetti did, the more my interest in the Afghani women who actually embroidered “Mappa” deepens as an embroidery artist. I wondered whether it was possible for me, as someone who does not live in a Western country either, to gain a deeper understanding of their techniques, their determination as craftspeople, and the amount of time they devote to their embroidery by embroidering a map of the world, being an embroidery artist myself. Boetti’s name and his map of the world has already become a recognized part of art history. However, wondering whether, for those of us living according to the reality we experience as we embrace all sorts of problems, there was not something more significant in shining a light on the activity of nameless embroiderers who have never had light shone on them before, rather than multiculturalism as an ideal, I came up with the idea of Map of the World (Dedicated to unknown embroiderers).

My experience of being an artist in residence in Aomori, where I stayed from the autumn through the winter of 2012, also significantly influenced this new work. In Aomori, first of all, I started with research of kogin-sashi, an embroidery technique that had been handed down to the people of Tsugaru, as a way of exploring the significance of producing works of embroidery on site. kogin-sashi, where geometric patterns are used to decorate kimono with the patterns of talismans against evil, is a beautiful and distinctive embroidery technique but originally, in the era when farmers were prohibited from using cotton, the weave of the coarse linen they used to make kimono was filled by means of embroidery to keep out the wind, and thus had a functional purpose. In other words, in the background to kogin-sashi, there is a history of suffering and also ingenuity by the women of the Tohoku region as a way of withstanding the severe cold and economic hardship. During my stay in Aomori, I had an opportunity to talk with the craftspeople who even today use the traditional kogin-sashi technique as well as the young craftspeople who are bringing a new approach to traditions, and it became a chance to rethink the significance of embroidery in different times in history and in different places. At the Hirosaki kogin-sashi Research Institute, I was able to pick up and examine beautiful, old pieces of embroidery made by unknown embroiderers of old. After going through this process, at the end of my stint as an artist in residence in Aomori, I made and presented works of embroidery on what looked like a pure white surface but from which traditional needlework patterns emerged in the darkness. In this work, the “extinction and revival” of tradition in the city was a major theme, and this is what led to my interest in the women who continue to embroider maps in war-torn Kabul.

Map of the World (Dedicated to unknown embroiderers) is a map of the world embroidered using a sewing machine. In bright light, it is a nondescript blank map, but in the dark, the different countries and their borders emerge. The borders that emerge then disappear, disappear then emerge. As the artist, I don’t know in what way the people who see the map regard it. However, if this work of embroidery were to live on as something left behind by a “nameless embroiderer” long after its creator has ceased to exist, it would bring this artist and his work the greatest happiness of all.

Satoru Aoyama

この作品はイタリアの前衛グループ、アルテ・ポーヴェラの一員として知られるアリギエロ・ボエッティの刺繍による世界地図作品、“Mappa”に対するオマージュとして長年構想していたものです。近年ロンドンのテイト・モダンで回顧展が開催されたり、ドクメンタ13で取り上げられたりと、批評的な側面から再評価されているボエッティですが、”Mappa”に対する自分の最初の印象は「良くできた工芸品」でした。それは決して肯定的な意味だけではありません。実際、“Mappa”が最初に発表された時、この作品は多くの批評家から工芸的だと酷評されたそうです。それは当時、アートはコンセプチュアルで高尚なものであり、技術を意味するクラフトは機能的な日用品である、というようにアートとクラフトがはっきり棲み分けされ、両者の間には価値的にも批評的にもヒエラルキーがあったことに由来します。(このヒエラルキーが形成された背景には社会に於ける女性の立場も関係しています。)もちろんボエッティは自分のアイデアを実現する為に必要な技術を職人に依頼するという、現代アートでは多く見られる方法で制作を行うコンセプチュアルな作家ですが、彼がアフガニスタンの首都、カブールのホテルを改装し、刺繍家たちを集め、制作を依頼した、という実際の背景を知らない者にとって、”Mappa”は国の領土にそれぞれの国旗の柄を当てはめた、刺繍による世界地図でしかありません。”Mappa”は当時にしては作家の個人性が極力排除された表現です。加えてボエッティは時に海の色など、作品にとっての重要な選択を刺繍家たちの判断に任せたりもしました。それ故、アートに携わる多くの人々に作品が工芸的だという印象を与えることとなりました。しかし、社会とアートを取り巻く状況が変わった現在では、ここに見られる「共同性」はボエッティの作品を再評価する大きな一因となっています。

一方、大学でテキスタイル科を専攻し、ミシン刺繍による作品を発表し続けている自分にとって、このアートとクラフトの関係性は常に重要な問題で、クラフト的な手法を肯定しながらアートの文脈に自分の作品を位置付けることは、現在まで続く制作の動機のひとつと言えます。それ故、ボエッティの活動の全容を知れば知るほど、”Mappa”を実際に縫っていたアフガニスタンの女性たちに対して同じ刺繍作家としての興味が湧いてきました。そして彼女たちの職人としての技術や決断、作品に捧げてきた時間を、同じ非西欧圏に住む、いち刺繍作家として世界地図を縫うことでより深く理解できるのではないかと考えました。ボエッティの名前と作品は既にアートヒストリーの一部として認識されています。しかし、この歴史上決して表舞台に上がることのない名もなき刺繍家たちの活動に光を当てることは、多文化主義を理想ではなく、あらゆる問題を内包しながらも実感を伴った現実として生きる自分たちにとって、より意義があることなのではないか、と考えたのが新作、“Map of the World (Dedicated to unknown embroiderers”を構想したきっかけとなっています。 また、2012年の秋から冬にかけて滞在した、青森でのアーティスト・イン・レジデンスの体験もこの新作に大きな影響を与えています。青森では、まず現地で刺繍作品を制作する意義を見つける為に、津軽に伝わる刺し子のひとつ「こぎん刺し」のリサーチから始めました。「こぎん刺し」は魔除けの柄等を着物にあしらった幾何学模様が特徴的な美しい刺繍ですが、元来、木綿の使用が農民に禁止されていた時代に、着物に使われている粗い麻布の布目を、刺繍で埋めながら防風性を高めるという機能的な目的から生まれました。つまり「こぎん刺し」の背景には厳しい寒さと経済的な困窮に耐える為の東北地方の女性たちによる苦悩と工夫の歴史があります。青森の滞在中には、現在でも伝統を守りながら刺し子をする職人さんや、伝統に新しい感性を吹き込もうとする若い職人さんとお話をする機会があり、刺繍というものが特定の時代や場所によってどのような意味を持つのかをあらためて考える契機となりました。また弘前こぎん研究所では、作者不明の古くて美しい刺し子を手に取って見ることができました。このような過程を経て、青森でのアーティスト・イン・レジデンスでは最終的に、伝統的な刺し子のパターン等が暗闇で浮かび上がってくる、一見真白な画面の刺繍作品を制作し発表しました。この作品では都市における伝統の「消失と再生」が大きなテーマとなっており、これは戦争に翻弄されながら、カブールで地図の刺繍を続けた女性たちに対する興味へと繋がっていきます。

“Map of the World (Dedicated to unknown embroiderers)”は、ミシン刺繍による世界地図です。明るい場所では何の変哲もない白地図ですが、暗闇の中では国名と国境が浮き上がります。浮かんでは消え、消えては浮かぶ国境が、観る人のどのような思いに触れるのか、作者の自分にはわかりません。ただ、この刺繍作品がもしも作者の存在を超えて、たとえ「名もなき刺繍家」が残した作品としてでも存在し続けられるなら、それは作者にとっても作品にとっても、この上ない幸せなことのように思えます。

青山悟

On Map of the World (Dedicated to unknown embroiderers)

This work, in the planning for many years, is a tribute to “Mappa,” the series of embroidered maps of the world by Alighiero Boetti, a key member of the Italian avant-garde group Arte Povera. Boetti has been critically reassessed in recent years through a retrospective exhibition at London’s Tate Modern and featuring at dOCUMENTA 13, but my own initial impression of “Mappa” was that they are “well-executed craftworks.” That does not necessarily only have a negative meaning. In fact, when “Mappa” was first shown to the public, it was apparently castigated by many a critic for being “craft-like.” At that time art was supposed to be something lofty and conceptual, and crafts that signified techniue were regarded as functional everyday objects. Art on the one hand and crafts on the other were segregated in this way, originating from the fact that between the two there was a hierarchy in terms of respective value and criticism. (The background that formed this hierarchy is also related to the position of women in society.) Boetti was of course a conceptual artist who produced his work using methods widely seen in contemporary art today, and hired craftsmen to implement the technique necessary to realize his ideas. However, for people who are unaware of the context in which “Mappa” came about, which is that Boetti was renovating a hotel in the Afghanistan capital of Kabul and commissioned a group of embroiderers to produce embroidery for him, “Mappa” would be nothing more than an embroidered map of the world showing national territories colored with the designs from each of their national flags. In line with the times, “Mappa” contains hardly any sign of the artist’s personality. Boetti would also sometimes entrust important decisions about the work, such as the color of the sea, to the embroiderers. This is the reason the work gives the impression of being craft-like to many people who are involved in art. However, in today’s world where the circumstances of society and art have changed, the nature of the situation where a group of people pull together towards achieving the same objective demonstrated by the “Mappa” project is one of the major reasons Boetti’s work is being reevaluated.

For me as someone who majored in textiles at university and since then has continued to exhibit works of sewing-machine embroidery, the issue of the relationship between art on the one hand and craft on the other is always important, and the positioning of my own work in the context of art at the same time as I affirm my craft-like techniques could be described as one of the motives of my artistic practice to date. The more I see the big picture of what Boetti did, the more my interest in the Afghani women who actually embroidered “Mappa” deepens as an embroidery artist. I wondered whether it was possible for me, as someone who does not live in a Western country either, to gain a deeper understanding of their techniques, their determination as craftspeople, and the amount of time they devote to their embroidery by embroidering a map of the world, being an embroidery artist myself. Boetti’s name and his map of the world has already become a recognized part of art history. However, wondering whether, for those of us living according to the reality we experience as we embrace all sorts of problems, there was not something more significant in shining a light on the activity of nameless embroiderers who have never had light shone on them before, rather than multiculturalism as an ideal, I came up with the idea of Map of the World (Dedicated to unknown embroiderers).

My experience of being an artist in residence in Aomori, where I stayed from the autumn through the winter of 2012, also significantly influenced this new work. In Aomori, first of all, I started with research of kogin-sashi, an embroidery technique that had been handed down to the people of Tsugaru, as a way of exploring the significance of producing works of embroidery on site. kogin-sashi, where geometric patterns are used to decorate kimono with the patterns of talismans against evil, is a beautiful and distinctive embroidery technique but originally, in the era when farmers were prohibited from using cotton, the weave of the coarse linen they used to make kimono was filled by means of embroidery to keep out the wind, and thus had a functional purpose. In other words, in the background to kogin-sashi, there is a history of suffering and also ingenuity by the women of the Tohoku region as a way of withstanding the severe cold and economic hardship. During my stay in Aomori, I had an opportunity to talk with the craftspeople who even today use the traditional kogin-sashi technique as well as the young craftspeople who are bringing a new approach to traditions, and it became a chance to rethink the significance of embroidery in different times in history and in different places. At the Hirosaki kogin-sashi Research Institute, I was able to pick up and examine beautiful, old pieces of embroidery made by unknown embroiderers of old. After going through this process, at the end of my stint as an artist in residence in Aomori, I made and presented works of embroidery on what looked like a pure white surface but from which traditional needlework patterns emerged in the darkness. In this work, the “extinction and revival” of tradition in the city was a major theme, and this is what led to my interest in the women who continue to embroider maps in war-torn Kabul.

Map of the World (Dedicated to unknown embroiderers) is a map of the world embroidered using a sewing machine. In bright light, it is a nondescript blank map, but in the dark, the different countries and their borders emerge. The borders that emerge then disappear, disappear then emerge. As the artist, I don’t know in what way the people who see the map regard it. However, if this work of embroidery were to live on as something left behind by a “nameless embroiderer” long after its creator has ceased to exist, it would bring this artist and his work the greatest happiness of all.

Satoru Aoyama